Architecture

Please note that this content is under development and is not ready for implementation. This status message will be updated as content development progresses.

Overview

The architecture is the blueprint for all the components of the specification and how they work together. It defines the design principles which underpin the UNTP and shows the components working together from the perspective of a single actor and across the entire value-chain. The UNTP is a fundamentally decentralised architecture with no central store of data.

Principles

The architecture principles that guide the UNTP design are

| Name | Principle | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| No dependency | UNTP should not require any collaboration or dependency between issuers, consumers and verifiers of DPPs | Imposing such collaboration as a pre-requisite for action in a complex many-to-many ecosystem would essentially stall progress |

| Unknown verifier | UNTP should not assume that that the consumer / verifier of UNTP data is known to the issuer, even when confidential data access is required | In a decentralised architecture with thousands of issuers, it would be impractical to register every authorised verifier with every issuer. |

| Any maturity | UNTP should not assume any technical maturity for verifiers | DPPs and other credentials must work equally for human and machine verifiers - otherwise an insurmountable complexity of knowing which customer has what capability would be required |

| Legacy data carriers | UNTP should work with any carrier of a product identifier including 1D barcodes, RFID tags, 2D codes and digital documents | 1D barcodes and RFID tags are ubiquitous and will only be replaced slowly. Uptake should not require manufacturers to re-instrument their production lines and printing processes |

| Verifiability | UNTP should provide confidence in the integrity and trustworthiness of the data | Without trustworthy data, the value of sustainability claims is reduced - possibly to the extent that the business case for adoption is non viable. |

| Any criteria | UNTP should not dictate any specific sustainability criteria but make the criteria transparent and allow criteria to be mapped (to achieve interoperability) | Costs will explode if every exporter must provide certification to every export market criteria. Where criteria are equivalent, mutual recognition provides a much more cost effective sustainability trajectory. |

| Action requires value | The benefits of UNTP implementation must exceed the costs. | If not then there will be no implementation |

UNTP conceptual overview

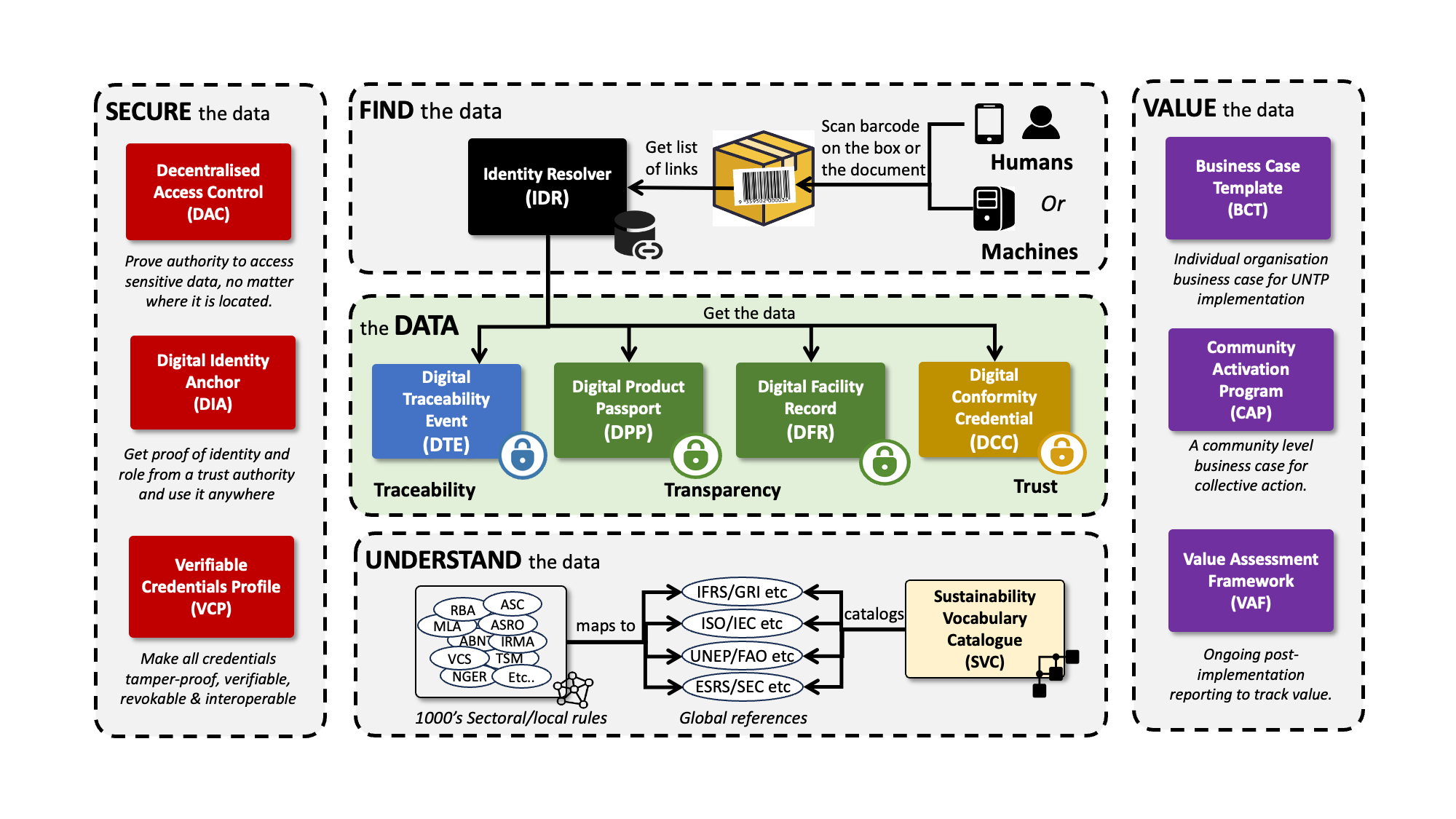

Our mission is to support global traceability and transparency at scale. To achieve that mission we must not only define the data standards but also solve all the barriers to adoption as scale. That includes how to find the data, how to secure the data, how to understand the data, and most critically, how to realise enduring business value from the data. These are the five pillars of UNTP.

Small scale tests are possible with any of these pillars missing but scalability to full production volumes is not.

The data

The data is the heart of the UNTP. There are four different data types.

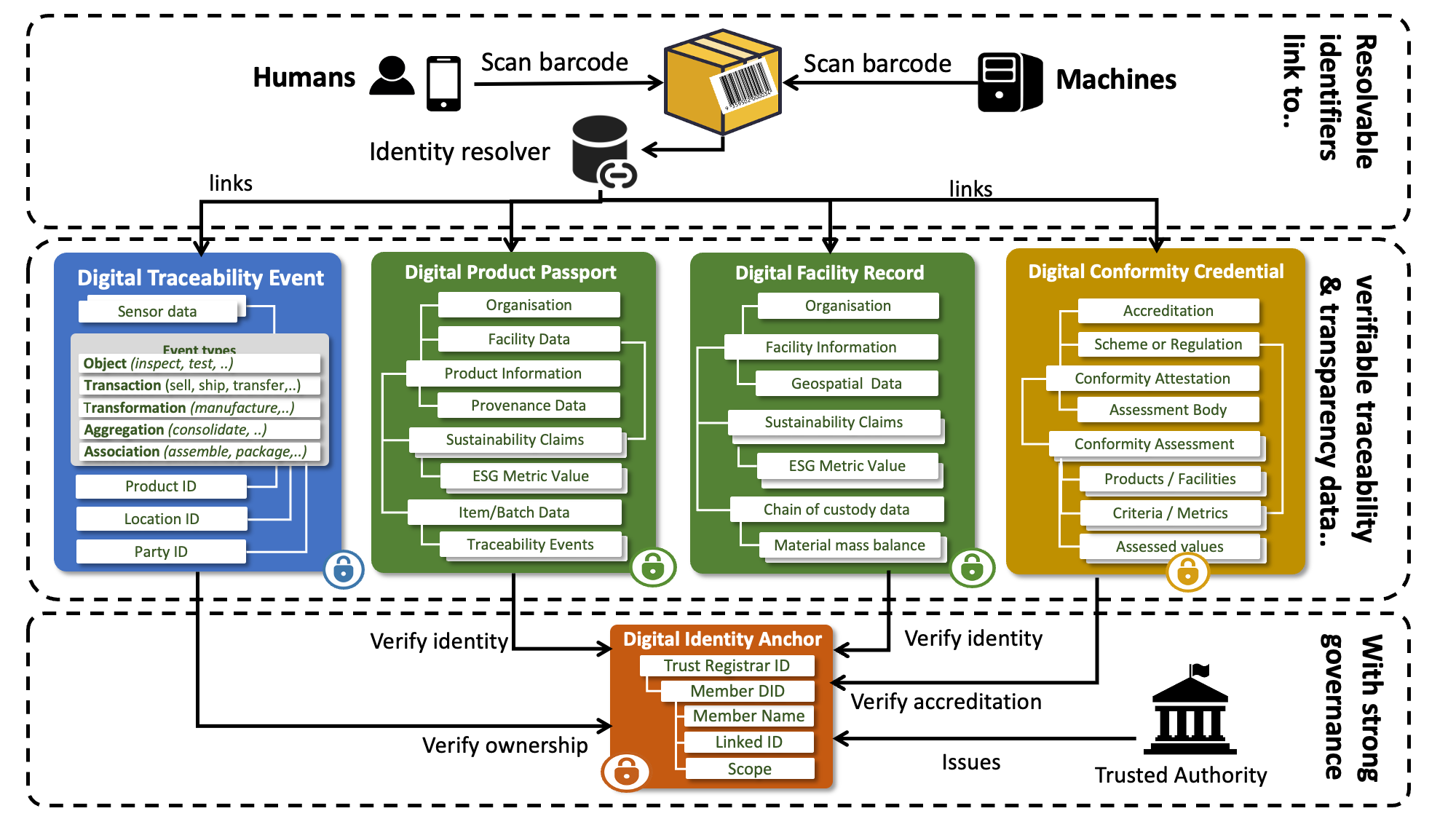

- The Digital Product Passport (DPP) is issued by the product manufacturer and is designed to carry basic product data plus the conformity data (including sustainability assurance data) that is needed by the next actor in the supply chain (ie the buyer of the product). The DPP represents the conformity information as a set of "claims" that specify product performance against specified criteria. In this way, the DPP is essentially a bundle of differentiated value that a buyer can use to choose a preferred supplier. The DPP also provides a statement of material provenance (ie what materials is this product made from and where were the materials sourced). The provenance data assist with ensuring conformance to minimum local content rules or sources under sanction.

- The Digital Facility Record (DFR) is issued by the owner or operator of a facility such as a mine, a farm, a material processing plant, a component manufacturing site, or a recycling plant. It is similar to a product passport but provides facility level information rather then product level information. The data includes some basic facility data, geolocated facility boundary information, data about bulk materials and product types produced by the facility, and a set of conformity claims (eg emissions footprint, deforestaiton status, etc).

- The Digital Conformity Credential (DCC) is issued by an independent auditor or certifier and it carries one or more "assessments" of an identified product or facility against well defined criteria. When the product ID and the conformity criteria in the DCC "assessment" match those in the DPP "claim" then the DPP data value is enhanced through independent verification. The DCC must include the identity of the accreditation authority and, where relevant, links to the accreditation authority, so that verifiers can be sure that the auditor or certifier is genuine.

- The Digital Traceability Event (DTE) provides a means to trace product batch data throughout the value chain. The DTE links input products (eg bales of cotton from the primary producer) to output products (eg woven cotton fabric). Therefore the DTEs provide a means to trace product provenance through manufacturing processes to discover an entire value chain. DTEs are only available when products are managed and traceable at batch level. DTEs provide links to reach deeper into the value chain which may contain commercially sensitive data and so may only be available to authorised roles.

All four UNTP data structures are designed to be extensible to meet the needs of specific industry sectors or jurisdictions.

Finding the data

We deliberately say "finding" the data rather than "exchanging" the data because a very critical principle is that the issuer of the data usually will not know who will ultimately use it. Obviously each seller knows their immediate buyer but many other actors in a circular economy may also encounter the identified product and need to access the DPP information. It follows that a key principle of UNTP is "if you know the identifier of a product then you can get the data about the product" - even many years after the product was created.

- Identity Resolver (IDR) specifications are a concretisation of ISO/IEC 18975 that provide a standardised way to resolve an identifier (of a product, batch, item, facility or entity) to a list of links (URLs) to further information about the identified object. The format of the linkset itself is defined by RFC9264. One identifier can resolve to multiple links, each of which is annotated with a specific link type (eg UNTP DPP). The IDR works with simple identifiers (eg encoded as a traditional 1D barcode) or complex identifiers (eg encoded as a QR code). In this way a single barcode or QR code can return a rich variety of information tailored to the requestor's needs. Furthermore, the IDR can return a collection of similar types of link with different date stamps or versions. One important use case for this capability to to return post-manufacture events such as consumption and eventual recycling of identified products.

Securing the data

As the value of sustainability attributes increases, so the temptation to make fake claims increases. Without confidence in the integrity of data, value is diminished. Additionally, as businesses publish more and more data about their products and upstream value chains, there is an increased risk of leakage of commercially sensitive information. Without confidence that sensitive data is accessible only to authorised parties, businesses will be less likely to participate. The UNTP security specifications address these challenges.

- Verifiable Credentials Profile (VCP). All UNTP data objects (DPP, DCC, DTE, DIA) should be issued as W3C Verifiable Credentials. This ensures that the data, once issued, cannot be tampered with, that the issuer is identifiable, and that status changes like revocation are immediately visible. The VCP defines a simple subset of the larger W3C specifications so that interoperability is simpler and cheaper to achieve. The VCP also includes an human-readable rendering template extension to the W3C specification so that anyone can verify UNTP credentials even if they have no technology maturity.

- Digital Identity Anchor (DIA). The issuers and subjects of Verifiable Credentials are identified using W3C Decentralised Identifiers (DIDs) which provide a means to discover the cryptographic keys necessary to verify the credentials. However, DIDs are self-issued and do not ensure that the issuer is really who they say they are, only that the owner of the DID was certainly the issuer of the credential. The DIA is a Verifiable Credential issued by a trusted authority (eg a government agency) that links a DID to a known public identity such as VAT registration number. In this way, verifiers can be assured of the identity of issuers. The DIA also has a "scope" so that, for example a national accreditation authority can attest to the identity of a certifier but also specify the scope of the accreditation.

- Decentralised Access Control (DAC). Not all traceability and transparency data for a given product is public information. Some is accessible only to authorised roles like a customs authority or a recycling facility. Some is accessible only to the verified purchaser of a product. In centralised systems, this kind of access control is managed by granting privileged access roles to authenticated users. But in decentralised systems such as the world of DPPs, this approach is not practical. There could be thousands of different platforms that host DPPs and it would be impractical for each authorised actor to create accounts on thousands of systems. The DAC defines a simple way to encrypt sensitive data with a unique key for every unique item and a way to distribute decryption keys to authorised roles without any advance knowledge about who has which role. Even if a decryption key is lost or leaked, the scope of data access is limited to one item. The DAC also provides a mechanism for the verified purchaser of an item to update the DPP record with post-sale events like consumption, repair, or recycling.

Understanding the data

The UNTP data objects (DPP, DCC, DTE, DIA) are deliberately simple so that they are easy to understand and low cost to implement. However a lot of the structural simplicity of a DPP is achieved via the "claims" object which is a simple abstraction that can carry any sustainability or conformity metric measures against any criteria from any standard or regulation. So this simple abstraction hides a world of complexity. In a world of thousands of standards or regulations, each with dozens or hundreds of distinct criteria, how can one claim about social welfare or biodiversity be meaningfully compared to another? How can an importer know whether a product sustainability criteria from an exporting economy is equivalent to the regulated criteria in the importer's economy? As a corporate subject to sustainability disclosures under IFRS or ESRS, how can I know how to match the claims in a received product passport with the impact areas of my disclosures statement? The UNTP cannot and should not dictate which sustainability standards or regulations any given claim or assessment references. However it can provide a way to map these criteria to a harmonised vocabulary to achieve interoperability.

- The Sustainability Vocabulary Catalog (SVC) defines a framework to map sustainability and compliance criteria across different standards, regulations and industry practices. The framework also allows unstructured product, facility, or entity evidence documents to be assessed against compliance criteria, indicating where there are gaps and opportunities to improve compliance. The framework is based on an AI architecture called Retreival Augmented Generation and aims to provide organsiations with a fast and efficient mechanism to quickly assess a complex set of compliance requirements.

As uptake of UNTP grows, maintenance of the SVC is one of the key activities that grows with uptake and adds continuously increasing value to the global sustainability effort.

Valuing the data

Without sufficient commercial incentive, businesses will not act. In some cases the commercial incentive is regulatory compliance. But few economies (The European Union is a notable exception) have current or emerging regulations that demand digital product passports for products sold or manufactured in their economy. However, there is much wider regulatory enforcement of annual corporate sustainability disclosures. But without sustainability data from supply chains at product level, there is no easy way for corporates to accurately meet their annual disclosure obligations. Worse, without product level data from suppliers, there is no way at all for corporates to select suppliers in such a way that they can demonstrate year-on-year improvements to sustainability performance. On top of the disclosure obligation, most corporates are very concerned about reputational risk associates with un-sustainable behaviour from their upstream suppliers. Furthermore, the financial sector is increasingly able and willing to provide improved financial terms for trade finance or investment capital to businesses with strong sustainability credentials. All these incentives drive behaviour and value but there is still some effort needed for each implementer to make a positive business case for change. UNTP offers some tools to determine the value that can inform a positive case for change.

- Business Case Template (BCT). A simple template for each role (buyer, supplier, certifier, software vendor, regulator, etc) to make a business case for the investment needed to implement UNTP. Continuously updated and improved with lessons from early implementations, the BCT provides a quick way for sustainability staff to support for their budget requests.

- Community Activation Program (CAP). Supply chain actors are often reluctant to proceed with a specific initiative like UNTP unless they have some confidence that others in their industry are doing the same. There are not only obvious interoperability benefits from industry-wide adoption but also cost benefits. For example, it is often the case that a small number of commercial software platforms are commonly used by larger numbers of businesses in a given industry and jurisdiction. So a software vendor that implements UNTP once will benefit all its customers. Additionally there are often a few standards and a few certifiers that are common to an industry and country. Likewise, there are very often one or more existing member associations that represent most of the actors in a given industry and country. Finally, when a large community is willing to act together, there will often be financial incentives from governments and/or development banks that can assist with initial funding. In short, there are many reasons to approach UNTP implementation at a community level. The CAP is a business template for a community level adoption of UNTP including a tool for financial cost/benefit modelling at community level.

- Value Assessment Framework (VAF). Once a community or individual implements UNTP and transparency data starts to flow at scale, it will become important to continuously assess the actual value that is realised. Dashboards and scorecards that measure key performance indicators will energise ongoing action and provide valuable feedback at both community and UN level. Therefore the UNTP defines a minimal set of KPIs that each implementer can easily measure and report to their community - and which communities can report to the UN.

UNTP for one actor

This section drills down a little into the key credentials that UNTP defines to answer "what's in a product passport or facility record or conformity credential or traceability event?". The diagram shows the perspective of one actor in the value chain that is publishing data about their faciliteis and products. The product identifier (at product, batch or item level) is the key for an Identity Resolver (IDR) to provide links to the UNTP credentials (and any other product related data). Every credential is both human and machine readable so that the same product scan will return a nicely formatted DPP and related data to a human scanning a barcode or QR code with their phone - or a structured digital data set to an automated scanner at the factory door.

Summary and detailed information about the content of each UNTP credential is available on this site and need not be repeated here

- Digital Product passport (DPP)

- Digital Conformity Credential (DCC)

- Digital Traceability Event (DTE)

- Digital Facility Record (DFR)

- Digital Identity Anchor (DIA)

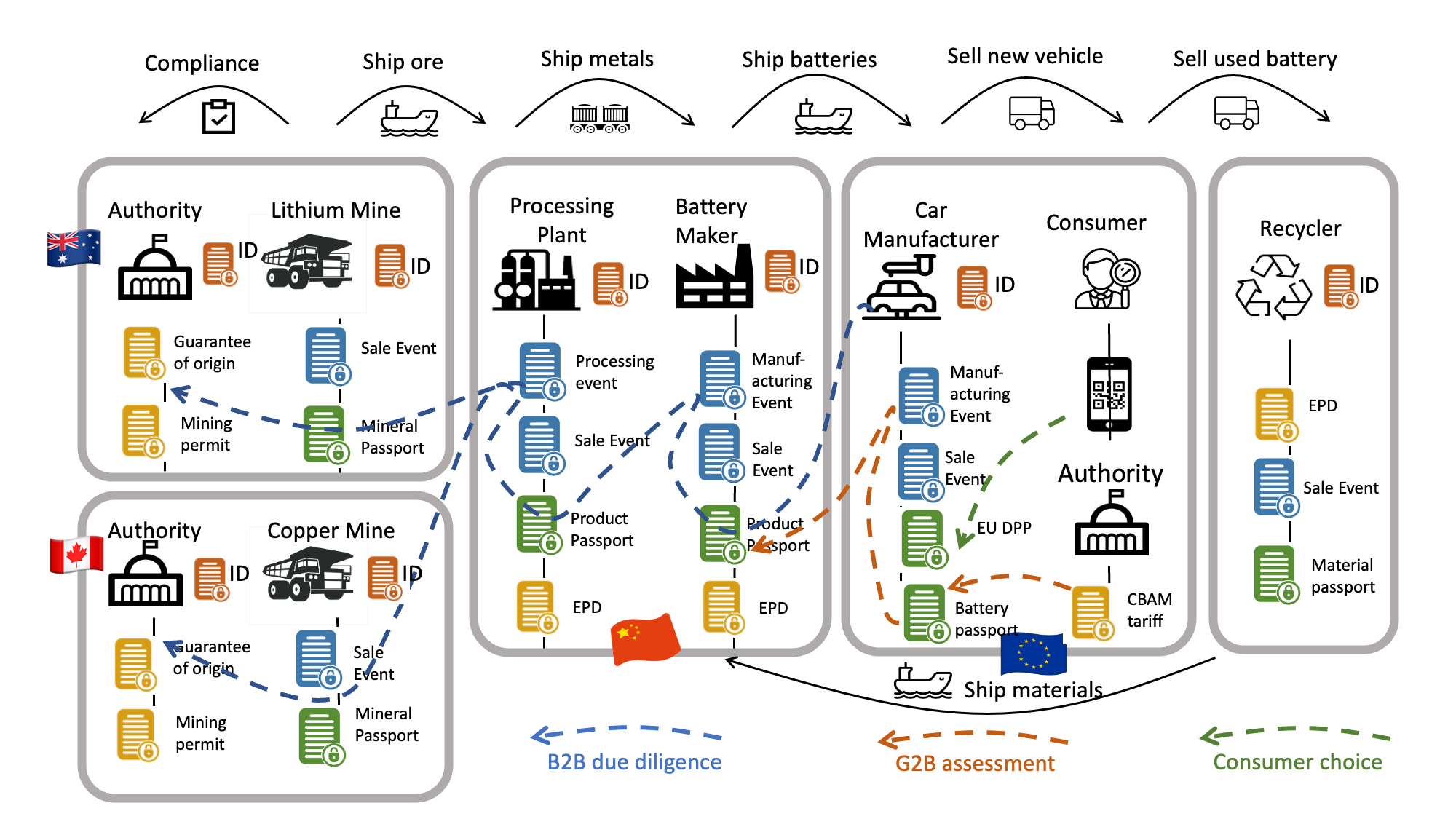

UNTP for a value chain

When each actor in a value chain implements UNTP then it becomes possible to trace product provenance across value chains back to primary production. There is no need for all actors in a value chain to collaborate or to implement at the same time. In many cases, the timing and incentives in different industry sectors of the same value chain will be very different. For example a leather goods manufacturer will usually be unable to influence the behaviour of cattle farmers because leather is a by-product and their focus in on the food value chain. Nevertheless, when an agriculture sector implements UNTP for their own reasons, the leather manufacturer can still access the data because UNTP provides a traceability mechanism that crosses industry boundaries without requiring collaboration between those industry sectors. In the example below, a battery can be traced to raw material production even when, from the perspective of the miner, the copper in the anode represents a tiny fraction of production.